The Reverend is a Rebel, Too

The Reverend is a Rebel, Too

By NOLI MANAIG

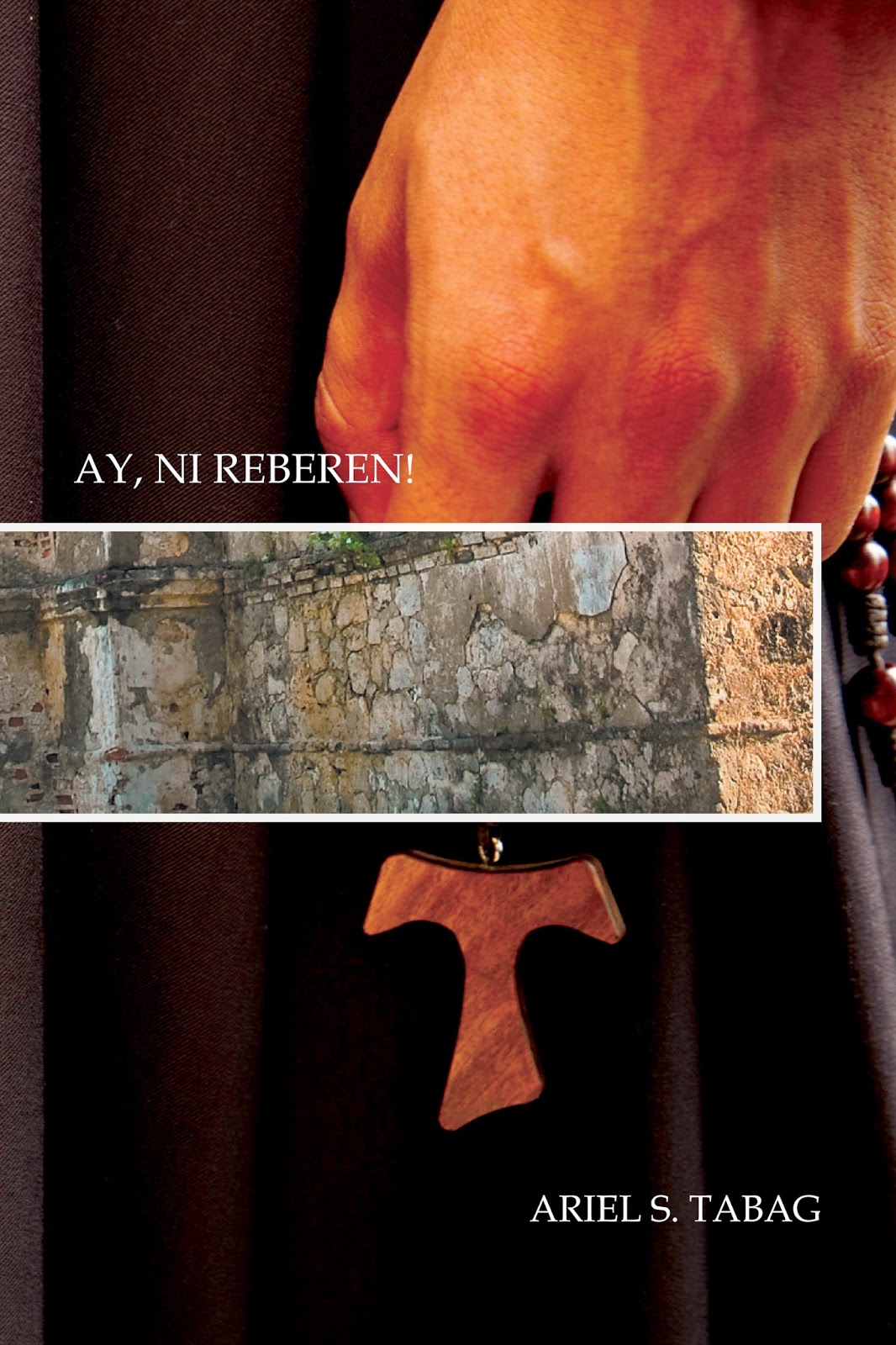

MEET Reverend Pascual Sotelo, Order of Friars Minor, the spitting image of a matinee idol wearing long locks of hair, a rock-‘n’-rolling, electric-guitar-wielding, high-fiving, pop-culture-loving would-be priest. In other words here is a protagonist that will make you do a double-take about what’s under the soutane— a counter-normative, counter-authoritarian would-be priest. It stands to reason, then, that he remains an unordained deacon, long overdue for priesthood, who, as the novel begins, gets a first taste of conducting a quasi-parish, on his own, somewhere in the backlands of Cagayan. It would be a mistake, however, to ascribe a wholesale irreverence and impiety to this man of the cloth. Despite worldly appearances, he may not be what he seems. Ay, Ni Reberen! then, in part, is about exploding stereotypes and strict dichotomies. But to a larger extent, this is about Reverend Sotelo’s passion, his worldly immersion, and the centrifugal forces around him that bring temptation.

As Ariel Sotelo Tabag’s debut novel, a comic, satirical one, serialized in Bannawag in 2013, Ay, Ni Reberen! exhibits the hallmarks of a well-crafted, counter-intuitive fiction, in keeping with the author’s unconventional alter-ego, the reverend bordering on rebellion. At some turning point in his life, Tabag himself had entered a seminary and is now a writer, plus a musician on the side— the namesake in the novel, true enough, embodies some of these designations— serving as his due diligence and research material, the better to shed light, with light-hearted inflection, the inner lives of liberal- minded priests.

Crafted for Bannawag’s rather diverse and popular readership Ay Ni Reberen! makes light of proceedings, disguises its purpose of ridicule and does not seem to make for a scandalous reading. That does not equate, however, with a whitewashed and sterilized novel: Tabag manages through a tongue-in-cheek literary touch to indict the excesses of all so-called high and mighty, and even lowly, walks of life: the military, the political, the religious, and most of all, the clerical, in this compact 100-plus pages of satire, not without a knowing wink or titter. Tabag manages this through the newly opened, once insulated eyes of an aspiring priest— hence giving the novel an aspect of a belated, adult bildungsroman— a deacon just getting his feet wet out of the cloister. But Reverend Sotelo is not necessarily a blank slate and knows things a priori, which the world only validates to his dismay.

A modulated form of stream of consciousness is thus the suitable and refreshing literary device of choice for this all-seeing, all-hearing novel. Here one oscillates between languages and codes, in what Mikhail Bakhtin calls dialogism, or polyphony, the novel encompassing many sounds and voices, popular, everyday speech leavened with the literary: from text messages to rock/pop/Christian song lyrics to earthy jokes, couched in English, Tagalog as well as anachronistic Spanish expletives, that swirl around this man of the cloth. Tongues wag in text messages, jokes insinuate and ridicule the guilty, song lyrics are tonics to strengthen the would-be priest, or express the tonality of the moment— one that sways between understanding, temptation, disbelief and dismay. So that Reverend Sotelo often repeats to himself this mantra: Bokasyon lang, walang personalan.

The oscillation between cacophony and euphony, a device wielded well to the author’s purpose, also affects how this highly contemporary novel circumvents the classical unities of time, space, and action. In keeping with periodical serialization, and the author’s undisguised penchant for cinema, Ay Ni Reberen! is constructed in self-contained episodes and results, in the process, into the attenuated build-up to its poignant denouement, something, however, made up for all throughout by a series of frissons that one gets as from divertissements of dedramatization in film.

The piquant irony of this novel is that, despite its express satire, it does not offend common sensibilities— whether religious, political or sociological. The novel’s subject matter is grounded in common knowledge, with human excess rendered in an incidental manner, but couched in Tabag’s seasoned and accomplished Ilocano prose, so that it can negotiate the pious and the earthy in one fell swoop.

In religious iconography— or is it also true in Christology?— Christ wears his hair long as a reflection of a free, truthful spirit. In Tabag’s novel, there is a moment when Reverend Sotelo undertakes the opposite route, an act of humility, a haircut, symbolic of his meeting halfway the worldliness of humanity, a compromise with the ways of the world, a sacrifice of what he might stand for, in fact. Its subtext is the old adage by John Donne: the life-giving interconnection and interrelation of men, so that compromise, not a holier-than-thou positioning, may be necessary.

Tabag’s affinity for popular culture and contemporaneity is also a strong presence in this first novel. Film, technology and pop and rock music, also finds expression in its character taxonomy and nomenclature. Bearing in mind the constraints of serialized writing, Tabag puts to use a literary shorthand where the heroes or the good are likened to Piolo Pascual or Bon Jovi and villains are unmistakably in the mold of Paquito Diaz and Leo Martinez. And somehow it works like a witty formulation, whereas an Emile Zola would spend chapter after chapter on dry, naturalistic description for the everyday things.

Rebellion, after all, is not a negative force but the antithesis in a dialectic— one to contrast and separate what is good and what is evil. Grounded in the context of corrupted Christianity, Tabag’s novel proves how appearances are not reality. The so-called well-appointed priests Reverend Sotelo comes to encounter are almost to a man in the pockets of politicians and businessmen, least of all not living their vows of poverty. So that in a more Catholic sense, Ay Ni Reberen! espouses a Buddhist-like appreciation of human capacities that forbid confinement to one designation. Is a priest just a priest? A rock’n’roller just a rock’n’roller? Christianity should take its cue from this and be all-embracing in its reach. Who even to choose between a rock’n’roller on the straight and narrow, or a depraved priest in all his fine regalia? The King Lear inside of us should see through present- day deception. Despite appearances, Reverend Sotelo may even surprise us, and prove to be the least-irreverent, least blasphemous of all the clergy. That is the irony of appearances contained herein. Rakenrol, Reverend!#

Comments

Post a Comment